The migrant crisis confronting Europe may well be seen by historians as one of those tipping points that alters the social fabric of the continent and its relationship with Africa and the Middle East, from where millions of people are trying to reach safety from war. Yet as European government’s ring their hands over the conflicting need to safeguard security and show compassion, reflecting fears of Muslim hordes reaching the gates of Vienna just as they did in the 16th century, it’s worth remembering that the flow of people has at other times been in the other direction.

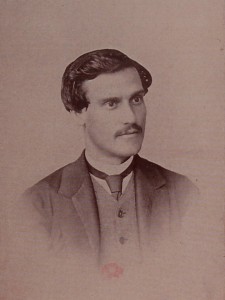

As the son of European immigrants whose antecedents populated the Levantine world in the Middle East, I am acutely conscious of the deep historical ties between the European and Arab world. My great great grandfather Samuele Sornaga, a Jew from Italy, fled nationalist turmoil of the 1840s to find safety and eventually considerable wealth and prosperity in Egypt under its late Ottoman rulers. My great grandfather Yannis Vatikiotis left the island of Hydra in the mid-1860s to seek better prospects on the coast of Palestine.

For Greeks, Italians, Maltese, and other peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean, the mid-19th century was a period of turmoil and uncertainty; by contrast, the Middle East was a land of opportunity and relative security. They flocked to the bustling Levantine capitals of Beirut, Alexandria, and Cairo, where they found jobs as artisans and functionaries for the modernising vassal states of the Ottoman Empire. In contrast to the obstacles to entry and citizenship that prevail in modern Europe, they obtained security under special laws that protected Europeans as French and British power took hold in the region.

They came, these Europeans, as refugees from war or migrants escaping economic depression and found not only wealth and security but also contributed a cultural and physical legacy, as seen in the language, art and architecture of contemporary Beirut, Alexandria and Cairo. They were largely welcomed – not only because the local rulers desperately wanted to modernise and fend off European colonial depredation, but also because of a basic form of religious and ethnic tolerance that late Ottoman rule fostered.

How ironic and so sad that war and upheaval, which has pushed close to four million Syrians out of their country, is also destroying the last vestiges of that rich religious and cultural pluralism that characterised the Middle East when my parents grew up there.

Early one morning the other day I jogged through Mon Repos Park in central Geneva, in the heart of Europe, almost stumbling over small huddles of homeless Africans and Middle Easterners sleeping under trees. Watching them rub their weary eyes and stare blankly at the trimmed and tidy city that for them is like a huge insurmountable wall, I reflected on my family legacy.

When Europe was in turmoil, convulsed by nationalist struggle and revolution, Italian Jews and Greek Christian islanders found shelter amongst the mainly Muslim forbears of these migrants. Like the mostly educated, middle class people trudging towards Austria and Germany today clutching smartphones and their branded apparel, many of the Europeans who left on steamers to the Middle East were educated, petit bourgeois traders and artisans.

Like the Syrians and Iraqis who aspire to be computer scientists and technology entrepreneurs in Germany, my Italian and Greek forbears harnessed their skills to the growth and development of their new homeland in the desert. My Greek grandfather Jerasimous Vatikiotis helped run the Hejaz railway; an Italian great uncle helped run the Post Office in Cairo.

Now, a century or more later, the Syrians and Iraqis have come in search of shelter. I bristle at the notion that we must somehow keep them out. How dare some European leaders speak of a ‘Muslim threat’ to a Christian culture. Doesn’t the threat, as such, stem from the current deep divide between the different religions of the book? Couldn’t we somehow help bridge that divide by integrating refugees from the great cities of Aleppo and Damascus into our own cosmopolitan centres?

It is heartening to see the warm welcome ordinary citizens have given to the refugees as they pour across the borders of Austria and Germany, proving that people are so much better than their governments, though I worry how long that welcome will last.

Both the Europe and the Middle East of today would seem alien to my Levantine ancestors. They would feel threatened by the violence and destruction generated by criminally enforced Islamic orthodoxy; but just as offended by the kind of rhetoric we have heard these past few weeks in Europe about a Muslim threat to Christian culture. One of my Greek forbears in Palestine helped defend the Holy sites for the Greek Orthodox Church. A great uncle rebuilt a Byzantine era Christian monastery on the road from Bethlehem to Jerusalem. The Khedives of Egypt liked to gamble, along with my Italian relatives.

Sadly, theirs is a lost era of tolerance and coexistence, and the reality today is the jackhammer in the hands of some nameless masked IS militant, who could for all we know be a European, chiseling off the ancient stone splendour of Palmyra. He will doubtless lose his life on some dusty desert road to a Hellfire missile, possibly fired by another European.